Synopsis

In this post, I will discuss how to set up variety of different meeting options on Zoom video conferencing for both scheduled class meetings and instant meetings or office hours with students. This tutorial will allow you to develop a singular link that can be used throughout the semester so your students will easily be able to use the same address every time you meet either for scheduled course time or for instant meetings. Zoom allows great flexibility with chat and content sharing with both its chat and screen-share options that allow real-time media sharing. Students are able to instantly follow along, receive materials, and focus on particular material even when they are not physically in the room.

Objectives

This post sprung from an impromptu workshop I did with some of my colleagues who had been using the Zoom platform and wanted to expand the functionality and ease of use of their experience by setting up a recurring class with a singular link. I myself found that with the switch to online learning prompted by the COVID-19 closures, Zoom became a standard go-to tool for meetings and coursework. It was not until I had continued to set up individual meeting after meeting to talk with my students, that I learned there was a way to streamline the process in a way that did not involve me creating and keeping track of dozens of meeting links and times. This lesson will look at the following objectives:

- Introduce how to set up a recurring semester-long course or meeting on Zoom with a singular link that can be imbedded into a learning management system.

- Demonstrate how to use your personal Zoom ID link to create an instant meeting with an individual or multiple persons.

Content/Instructions

Setting up a recurring meeting:

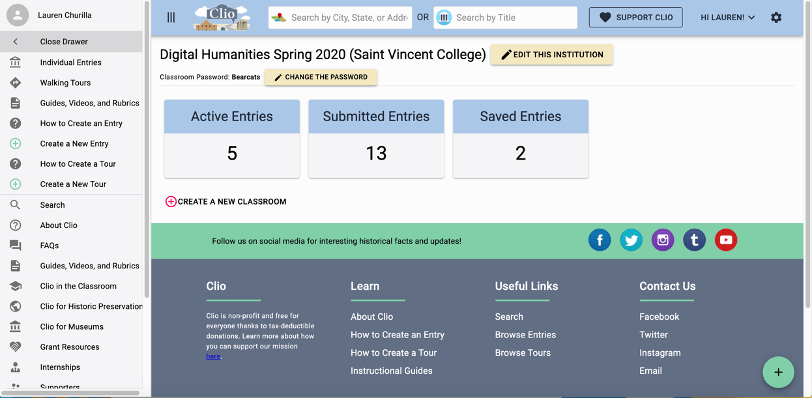

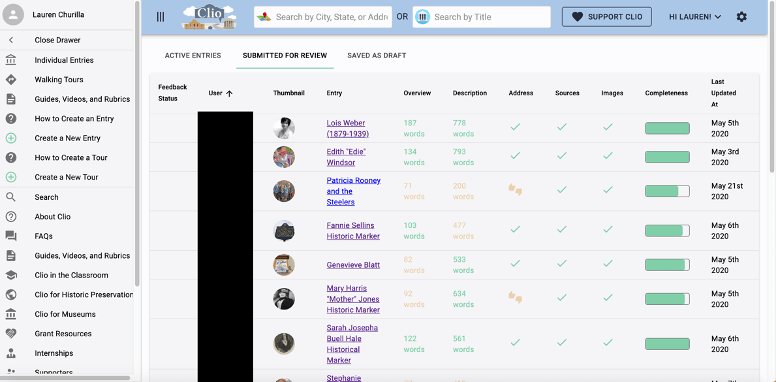

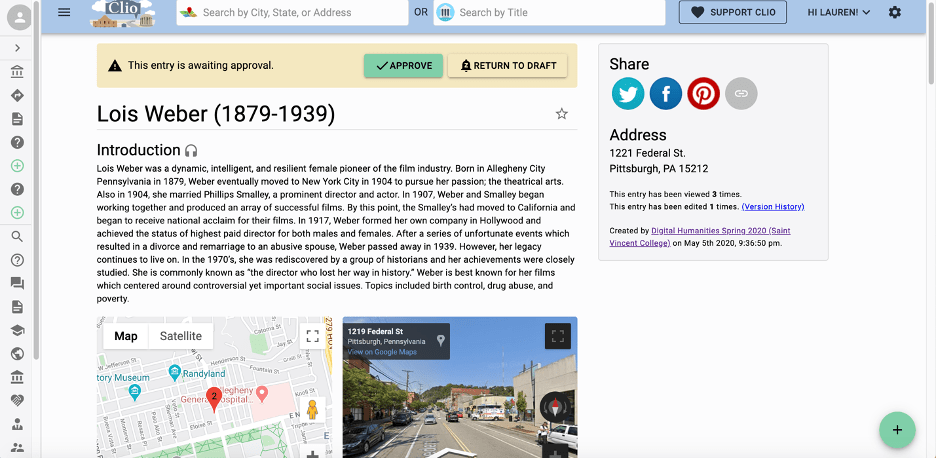

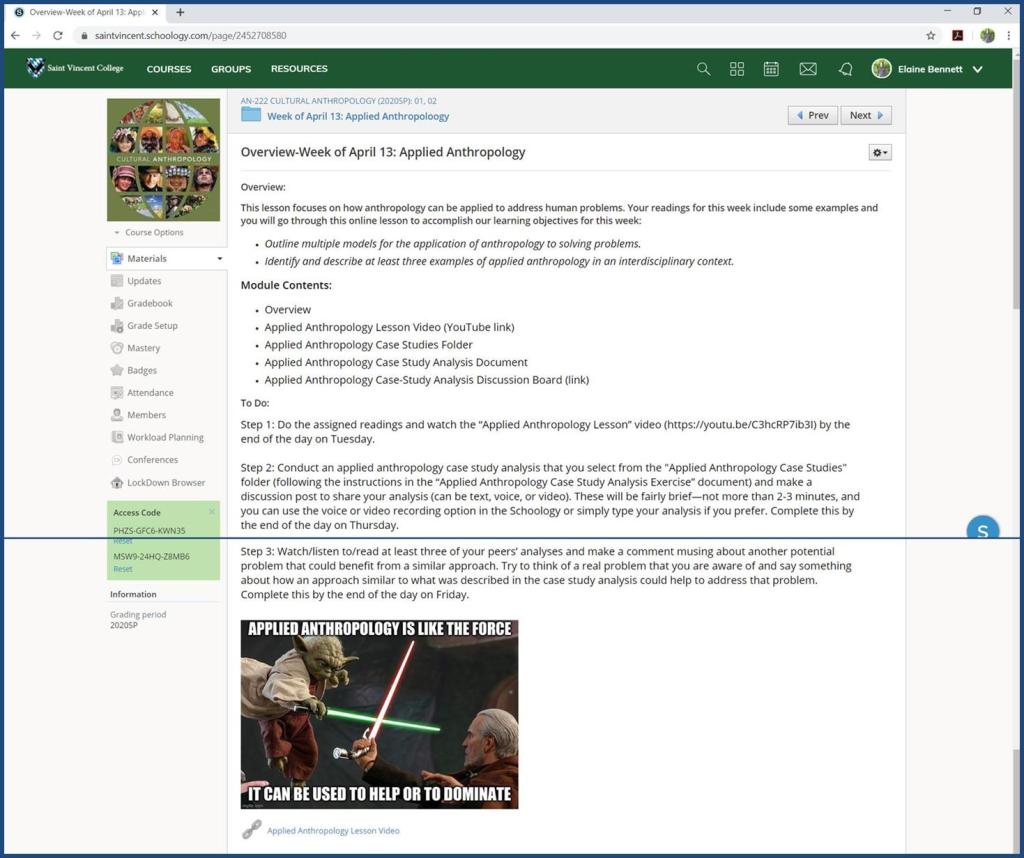

When you login to Zoom, you will be able to set up instant or scheduled meetings. These meetings appear on your dashboard like mine do in my example below.

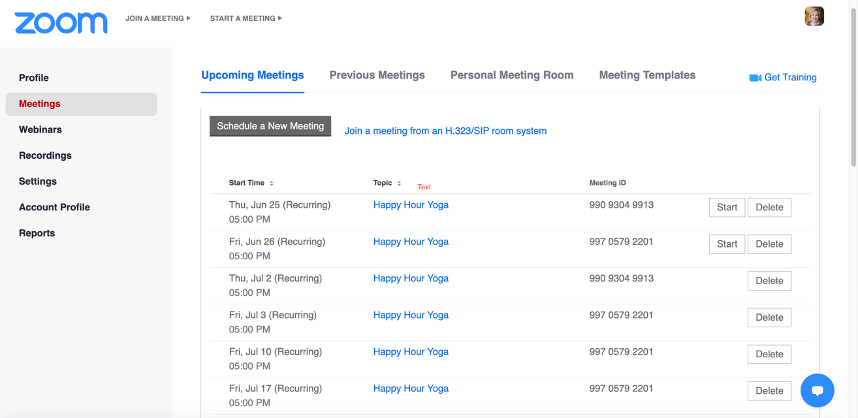

- The first step to setting up a recurring meeting is to click “Schedule a New Meeting” located in the top left quadrant of the page in the gray box. This will bring you to the screen you see below:

2.

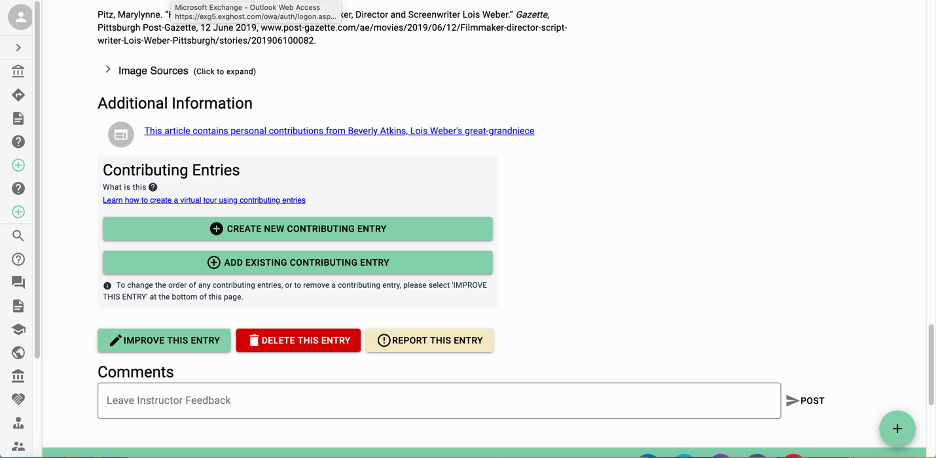

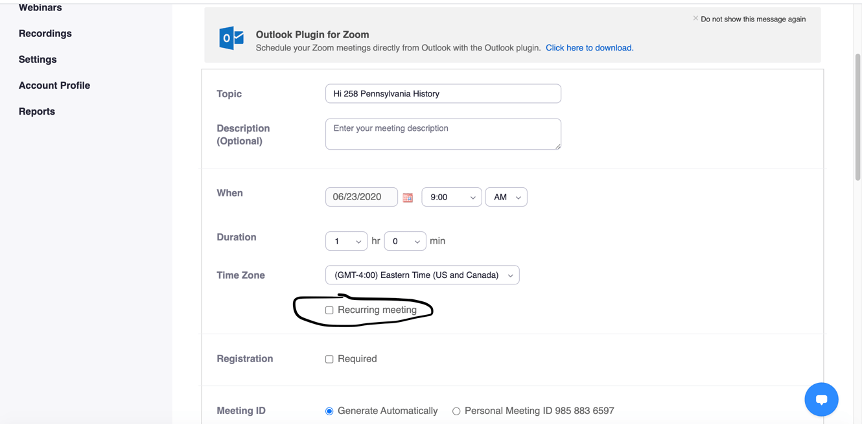

- Enter your course name and then click the box called “recurring meeting.” Once selected, the options below will appear.

- In the “When” box, select the date of your first meeting and the starting time.

- In “Duration,” select the length of the meeting. I am teaching a once a week class that lasts 2.5 hours with a start date of August 18, 2020.

- After this, you can select the meeting’s recurrence. Zoom allows you to select daily, weekly, monthly, and no fixed time meetings. I have chosen weekly since my class meets once a week. If your class will be meeting multiple times, simply select all of the weekdays days that the course will meet synchronously.

- You then have the option to select an “End date.” I find it easier to put in a calendar date than select the number of occurrences option. My course meetings will end the week before Thanksgiving, so I have selected the last day of class as the end date.

- After this, you can scroll down and set up the rest of your meeting options.

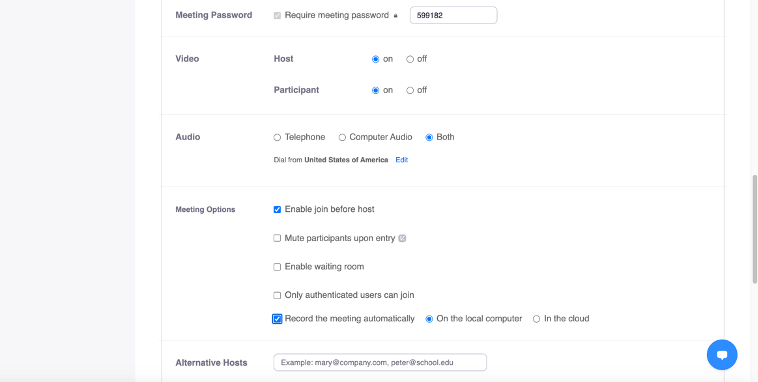

- Here you can select if you would like your participants to have their video on. For a small class or discussion-based class, I find it best to allow video so your students can see each other when they are talking and it allows for a more personal feel. However, if you are presenting a lecturer, turning off participants video may be lest distracting and will help save bandwidth usage. You can turn off participants video at any time, but only they can turn it back on.

- Students without a microphone may choose to dial in on the phone in order to talk on the conference. I always select “Both” audio options.

- In “Meeting Options,” you can select the settings you would like. “Join Before Host” allows students to enter the classroom, even if you have not yet logged in. I prefer this option because it gives students some time to socialize.

- If you “Enable waiting room,” you must manually admit students or participants as they request access. Some people prefer this as it lessens the opportunity for strangers to join your meeting and be disruptive.

- If you are going to post the lecture online when you are done, I would recommend the “Record the Meeting Automatically” function. This way, you do not need to remember to hit record for every lecture. This function is nice because it will allow you to save and post the class so anyone who was not able to make it to the live meeting.

- If you are team teaching, you can add another host into the meeting in the “Alternative Host” box. By giving another person hosting privileges, they can also mute and unmute participants or remove disruptive persons from the meeting.

- Finally, click the “Save” button:

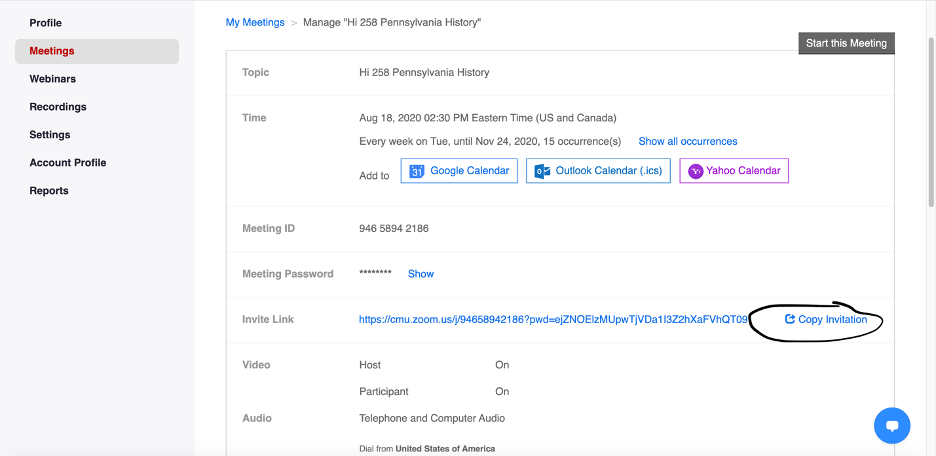

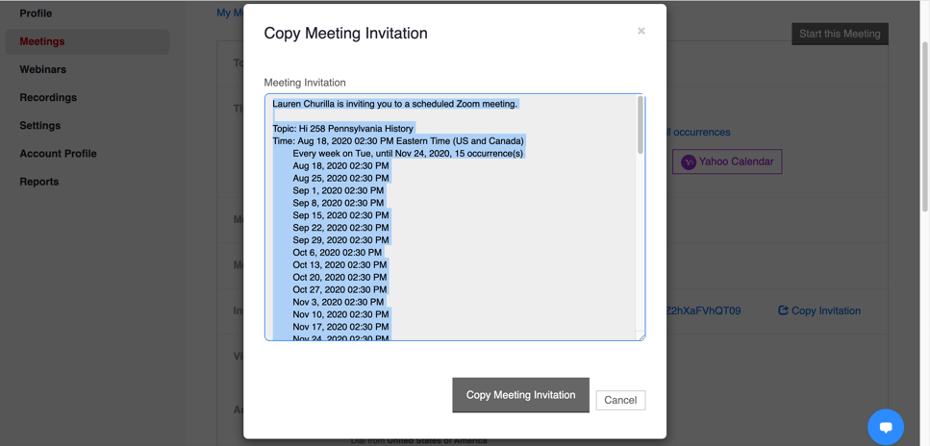

15. When you are done, a meeting link will generate. In order to share this with you class, copy the invitation by clicking the link circled below:

16. This invitation can be shared via email or embedded into a learning management system.

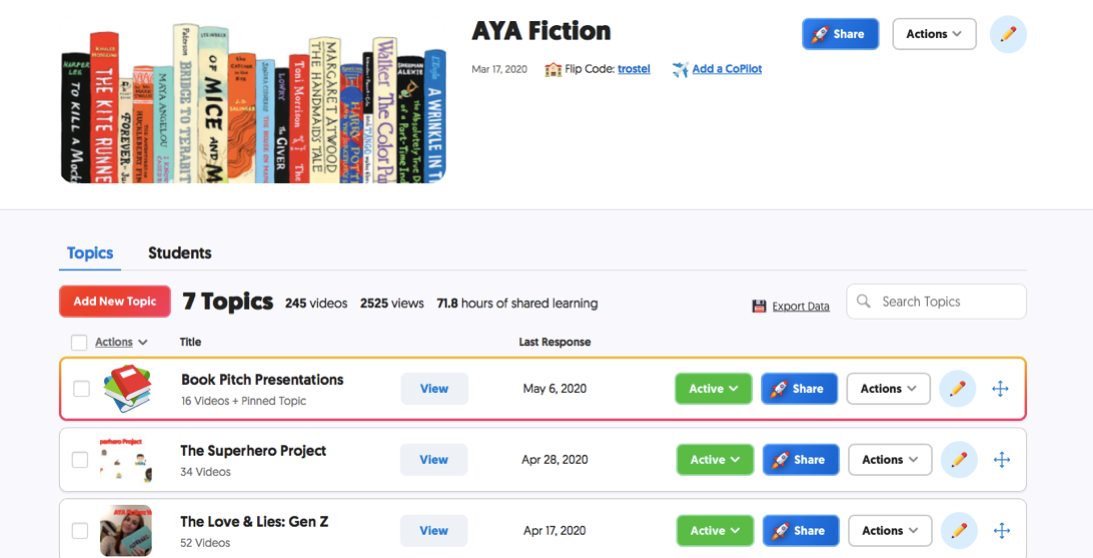

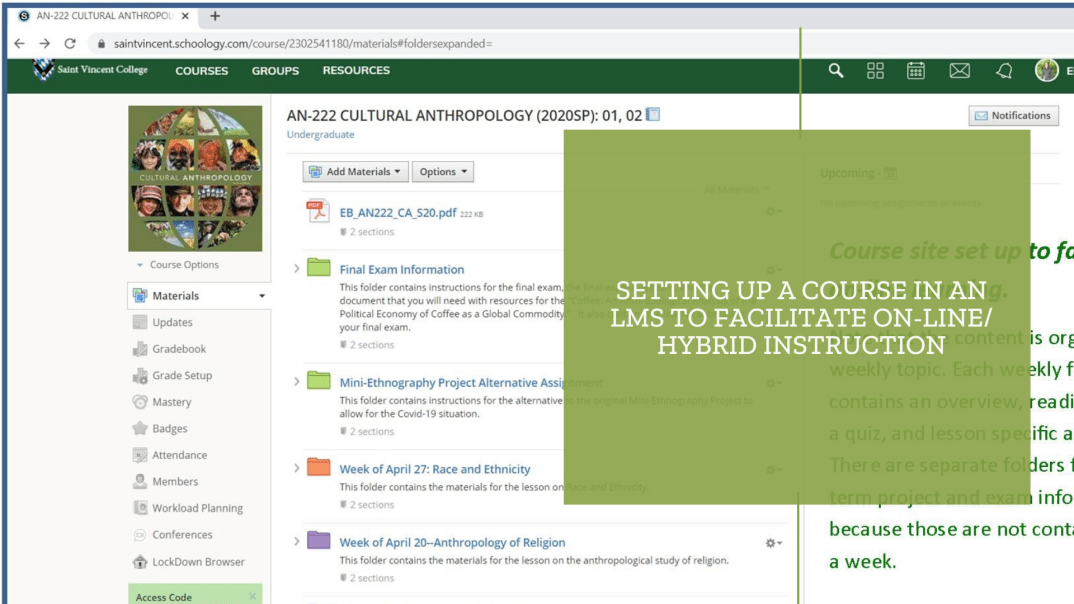

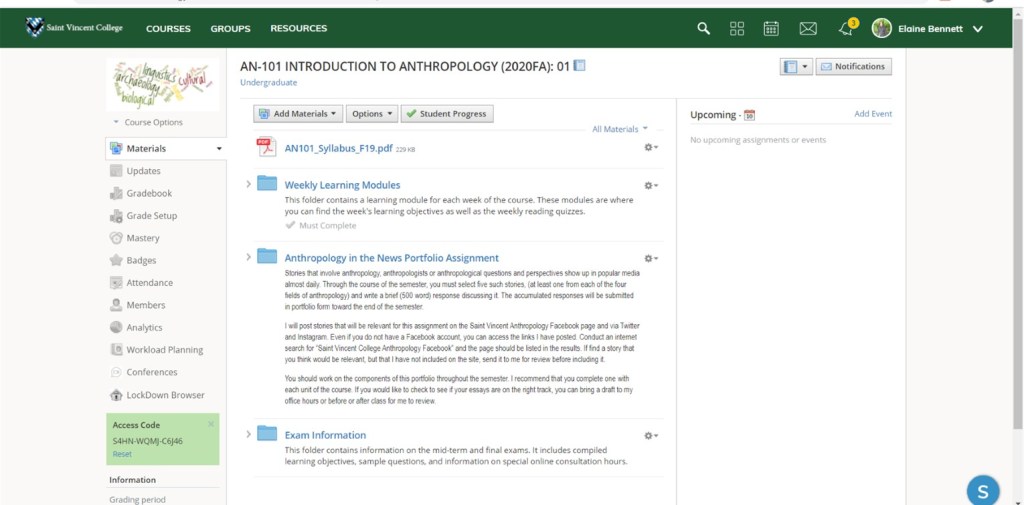

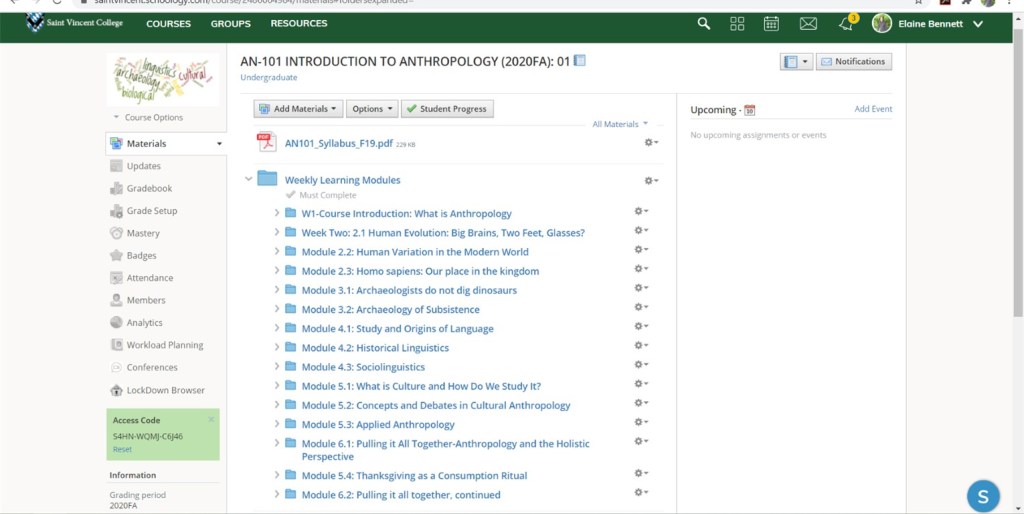

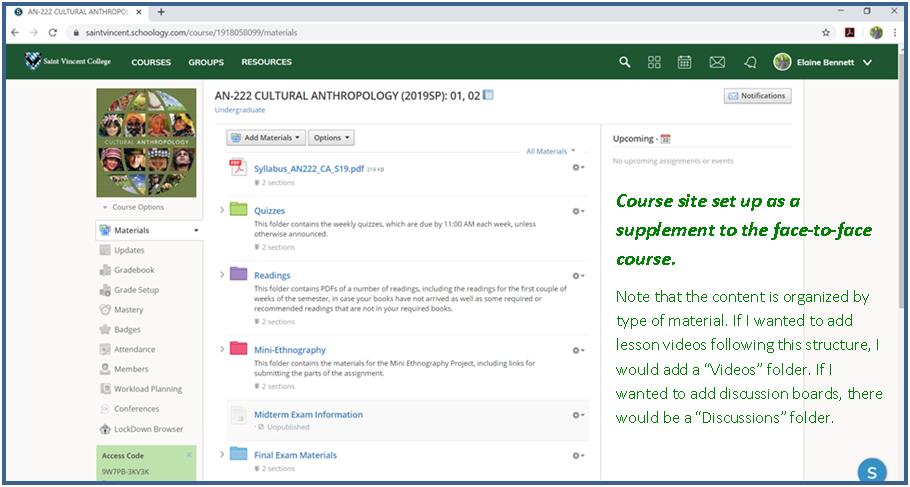

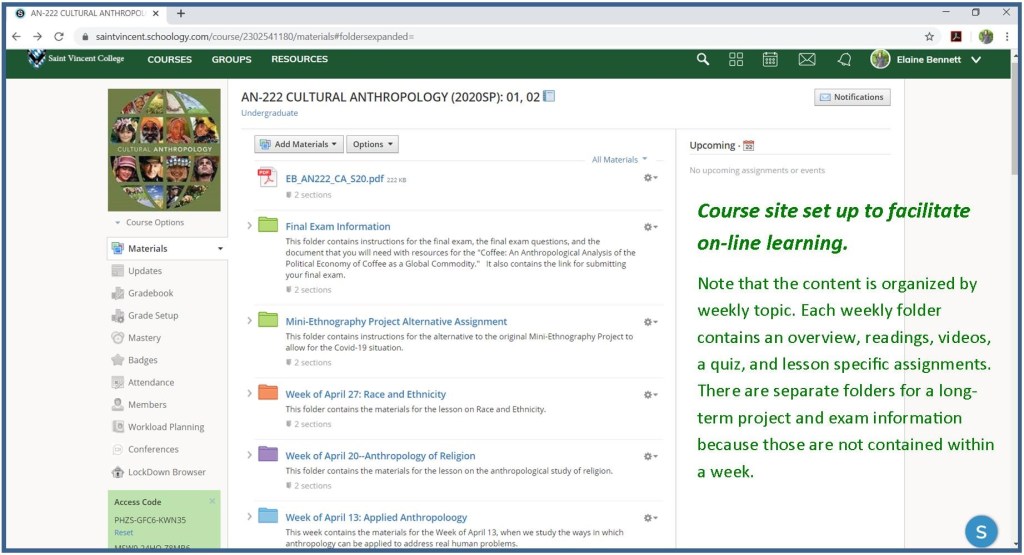

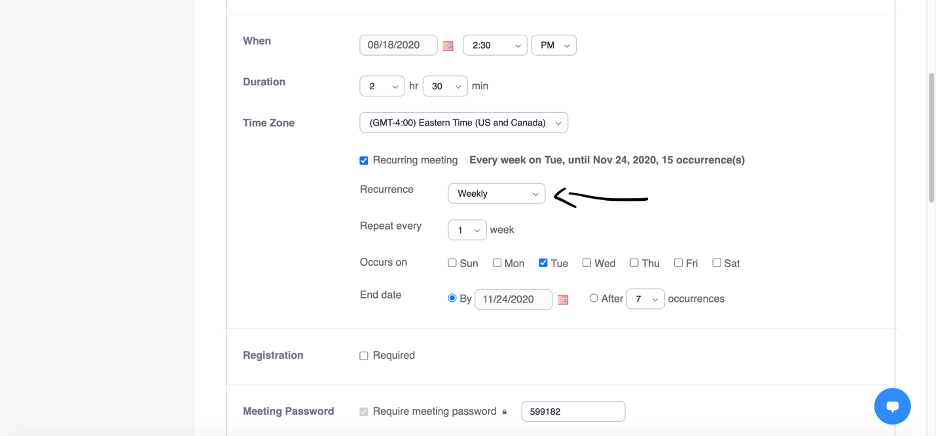

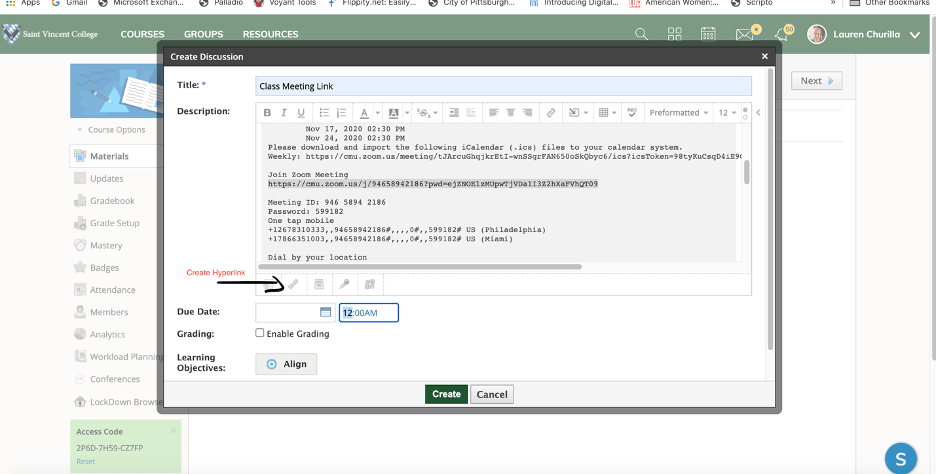

- I am embedding my meeting into Schoology so that my students will easily have access to the link. I created a folder called “Class Meeting Link” and posted the full invitation. For ease of access and for students who do not want or need to scroll through all the information in the full invitation, I created a hyperlink for the “Join Zoom Meeting” link using the hyperlink tool in our LMS.

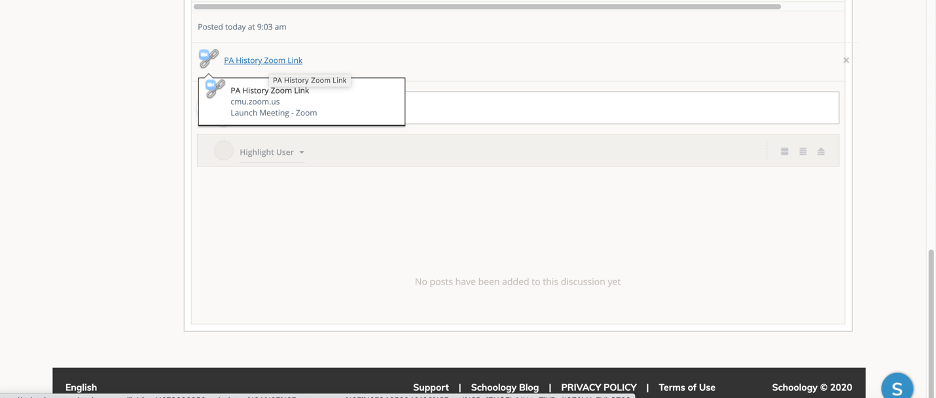

- The final result will be an easy link for students to click on to enter the Zoom class. Both instructor and student will use the same link every time and the link will work for the duration of the semester.

Setting up an instant meeting:

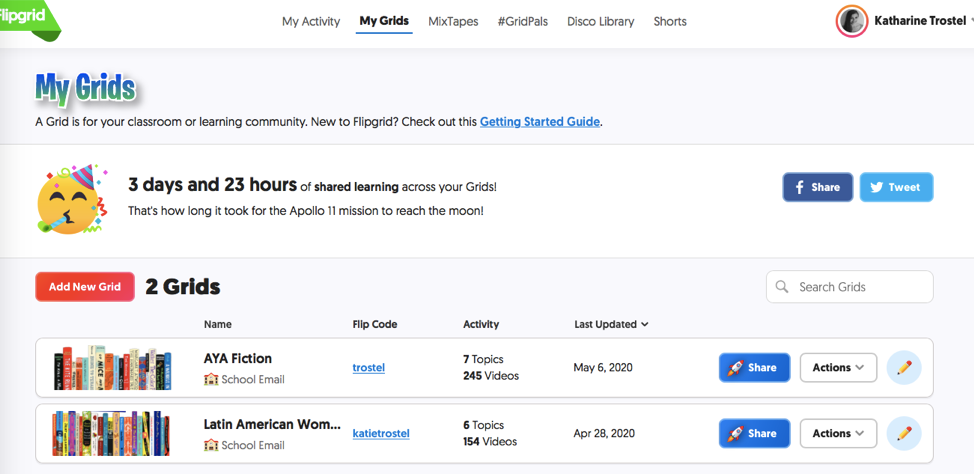

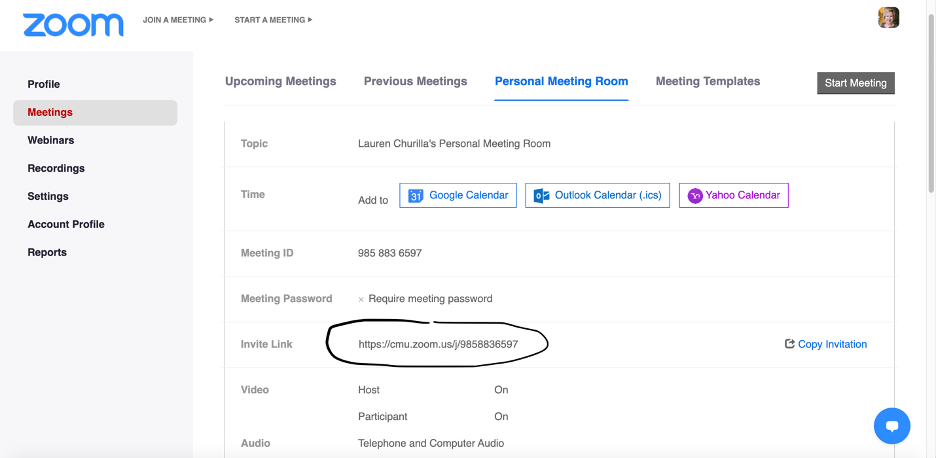

- Go to your personal meeting room.

- Copy your personal meeting link and follow steps 18 and 19 above. I typically will embed my personal meeting link into my LMS as “Office Hours.” This link will allow you to meet with anyone at any time instantly without setting up a meeting.

Positives/Challenges

Positives:

- Zoom allows synchronous teaching with students that includes the ability to visually see a large number of students, allows audio and screen sharing, and can be used for text chatting. Course material can be distributed in real time vie the chat function or through screen sharing.

- Automatically enabled recording or the ability to record quickly and easily converts the lecture or meeting to a video file that can be saved or distributed to participants not able to join in real time.

Challenges:

- Zoom can sometimes have technical difficulties. It is very important to have sufficient bandwidth if you will be using full video capabilities with students or participants. Without this, sound and video tend to cut out or freeze making it difficult to have easily conversation. This can be solved by making sure the host has sufficient internet capabilities or my muting the video footage of participants. The lack of bandwidth can be particularly difficult for students living in areas that have less digital infrastructure and are functioning with lower speed networks.

- Time planning can be a bit challenging as students may not enter the classroom at the same time and may come in a bit late. This can be solved by recording classes for students who may not have been able to join or fully participate in real time. Additionally, be prepared to not have the full time of the class to teach, as you may feel like things take a bit longer on a conference.

- Without a paid subscription, Zoom meetings are limited to 40 minutes for anyone not in a K-12 educational setting.